April 2024: China’s New Tariff Law and “Law-Based Taxation”

New Degrees Law and remedies for degree denial and revocation. Six bills for public comment. Plus: AI lecture to lawmakers.

Welcome back to NPC Observer Monthly, a monthly newsletter about China’s national legislature: the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee (NPCSC).

Each issue will start with “News of the Month,” a recap of major NPC-related events from the previous month, with links to any coverage we have published on our main site, NPC Observer. If, during that month, we have also written posts that aren’t tied to current events, I’ll then provide a round-up in “Non-News of the Month.” Finally, depending on the month and my schedule, I may end an issue with discussions of an NPC-related topic that is in some way connected to the past month.

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it. —Changhao

News of the Month

On April 16, the Council of Chairpersons decided to convene the 14th NPCSC’s ninth session. The Council also approved the NPCSC’s 2024 work priorities as well as 2024 plans for legislative, oversight, and delegates-related work, which have just been released. I’ve already covered the legislative plan here and will discuss the others in the next issue of this newsletter.

On April 23–26, the 14th NPCSC met for its ninth session and approved three bills: the Degrees Law1 [学位法]; the Tariff Law [关税法]; and technical amendments to three laws. I’ll first go through the amendments and other news from the session, before returning to the two meatier laws below.

The amendments serve to implement the 2023 State Council Institutional Reform Plan and an undisclosed plan issued by the Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council on “optimizing and adjusting deliberative and coordinating bodies [议事协调机构].”2 Specifically, the bill—

amended the Agricultural Technology Popularization Law [农业技术推广法] by removing the authority of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and its local counterparts to “guide efforts to popularize agricultural technologies”;

amended the Minors Protection Law [未成年人保护法] to reflect the fact that the State Council’s Leading Group on Minors Protection had been absorbed by the State Council’s Working Committee on Women and Children; and

amended the Biosecurity Law [生物安全法] by vesting MOST’s regulatory authority over human genetic resources in the National Health Commission instead.

In addition to the three approved bills and the six bills later released for public comment (see below), the NPCSC also reviewed the State Council’s request for authorization to temporarily modify unspecified provisions of the Food Safety Law [食品安全法] in the Hainan Free Trade Port (which covers the entire Hainan Island). Strangely, the NPCSC did not approve the request as expected, nor has there been any media coverage of it. For the dozens of reform authorizations that the NPCSC has granted since late 2012, it approved all but one3 after just a single review. It is unclear if the State Council’s request was facing resistance in the legislature or if the NPCSC has decided to take a bit more time reviewing such requests going forward.

Finally, after last month’s session, lawmakers listened to a lecture on “the development of artificial intelligence [AI] and intelligent computing” [人工智能与智能计算的发展] by Sun Ninghui [孙凝晖], a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and academic head of the Institute of Computing Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The NPCSC regularly organizes such “topical lectures” [专题讲座] to equip lawmakers with the basic knowledge relevant to future legislation, although this doesn’t necessarily mean that an AI Law will come before the NPCSC anytime soon.

The full transcript of Sun’s lecture is available here, and the Geopolitechs newsletter offers a partial English translation. The lecture discusses the history of computing technologies and intelligent computing, the security risks posed by AI, the dilemma facing the development of intelligent computing in China, and the possible paths China may choose from. He had this to say on a future AI Law:

China should accelerate the enactment of an AI Law so as to construct an AI governance system, ensure that the development and application of AI follow the common values of humankind, and promote human-machine harmony and friendship; create a policy environment conducive to the research, development, and application of AI technologies; establish reasonable disclosure mechanisms as well as audit and evaluation mechanisms, and understand the principles and decisionmaking processes of AI mechanisms; clarify the security obligations of and accountability mechanisms for AI systems, and make liable parties traceable and remedies available; and promote the development of fair, reasonable, open, and inclusive international rules on AI governance.

我国应加快推进《人工智能法》出台,构建人工智能治理体系,确保人工智能的发展和应用遵循人类共同价值观,促进人机和谐友好;创造有利于人工智能技术研究、开发、应用的政策环境;建立合理披露机制和审计评估机制,理解人工智能机制原理和决策过程;明确人工智能系统的安全责任和问责机制,可追溯责任主体并补救;推动形成公平合理、开放包容的国际人工智能治理规则。

On April 26, the NPCSC released the following bills for public comment through May 25, 2024:

draft revision to the National Defense Education Law [国防教育法];

draft amendment to the Accounting Law [会计法];

draft amendment to the Statistics Law [统计法];

draft Energy Law [能源法];

draft Atomic Energy Law [原子能法]; and

draft revision to the Anti–Money Laundering Law [反洗钱法].

English translations and comparison charts, where available, can be found on the bill pages.

Degrees Law

This Law (translated here), upon taking effect on January 1, 2025, will replace the 1980 Degrees Regulations [学位条例], one of the first laws the NPCSC passed in the Reform Era. The Law maintains the three tiers of degrees under the Regulations—bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees—and the overall regulatory structure headed by the State Council Degrees Commission. The Law also makes the following key changes:

statutorily dividing degrees into academic and professional degrees and articulating separate requirements for obtaining professional degrees (see arts. 2, 20–21);

formally incorporating provincial-level degrees commissions into the regulatory structure and memorializing their role in prescribing specific requirements for obtaining degree-conferring qualifications and in reviewing applications for such qualifications (see arts. 12, 14–15, 34);

clarifying the criteria and procedures for granting degree-conferring qualifications to universities and other institutions (see Ch. II);

adding a separate chapter on “safeguarding the quality of degrees” (see Ch. VI); and

affording degree candidates more procedural protections in degree-related disputes with their institutions (see arts. 39–41).

Focusing on the last point for a moment. Under the Law, an educational institution may refuse to grant a degree or may revoke a degree already granted if the degree applicant or holder has one of the following circumstances (art. 37):

(1) where the dissertation or practical result [实践成果, which applies to professional degrees] has been ascertained to involve academic misconduct, such as ghostwriting, plagiarism, or falsification;

(2) stealing or fraudulently using another’s identity to obtain the admission qualifications obtained by the latter, or using other unlawful means to obtain admission qualifications or certificates of graduation;

(3) engaging in other serious unlawful conduct while studying for the degree based on which the degree shall not be conferred according to law.

Before the institution makes either decision, however, the Law requires it to notify the individual of its proposed decision as well as the facts, reasons, and basis therefor, and to hear the latter’s statements or defenses (art. 39). These basic due process requirements are identical to those that administrative agencies must follow before imposing administrative punishments.

The Law does not, however, straightforwardly grant degree applicants and holders the same remedies as one has against administrative punishments. Under the draft released by the Ministry of Education in early 2021, an individual could indeed challenge an institution’s adverse decision through administrative reconsideration or administrative litigation (after having exhausted the institution’s internal review). Then the draft from 2023 would allow for only an internal review by the institution and a further appeal to the relevant provincial-level degrees commission. This process was again modified in the Law’s final version, which allows an individual to either seek an internal review or “request that the relevant organs handle [the dispute] in accordance with the provisions of law” (art. 41).4

The latter remedy likely still includes administrative litigation, as it appears settled in practice that an institution’s refusal to confer degrees or its revocation of degrees may be challenged in court. Maybe the Law eschews using those exact words because an educational institution’s statutory power to grant degrees is not quite typical administrative power.5 Still, some more clarity would be helpful.

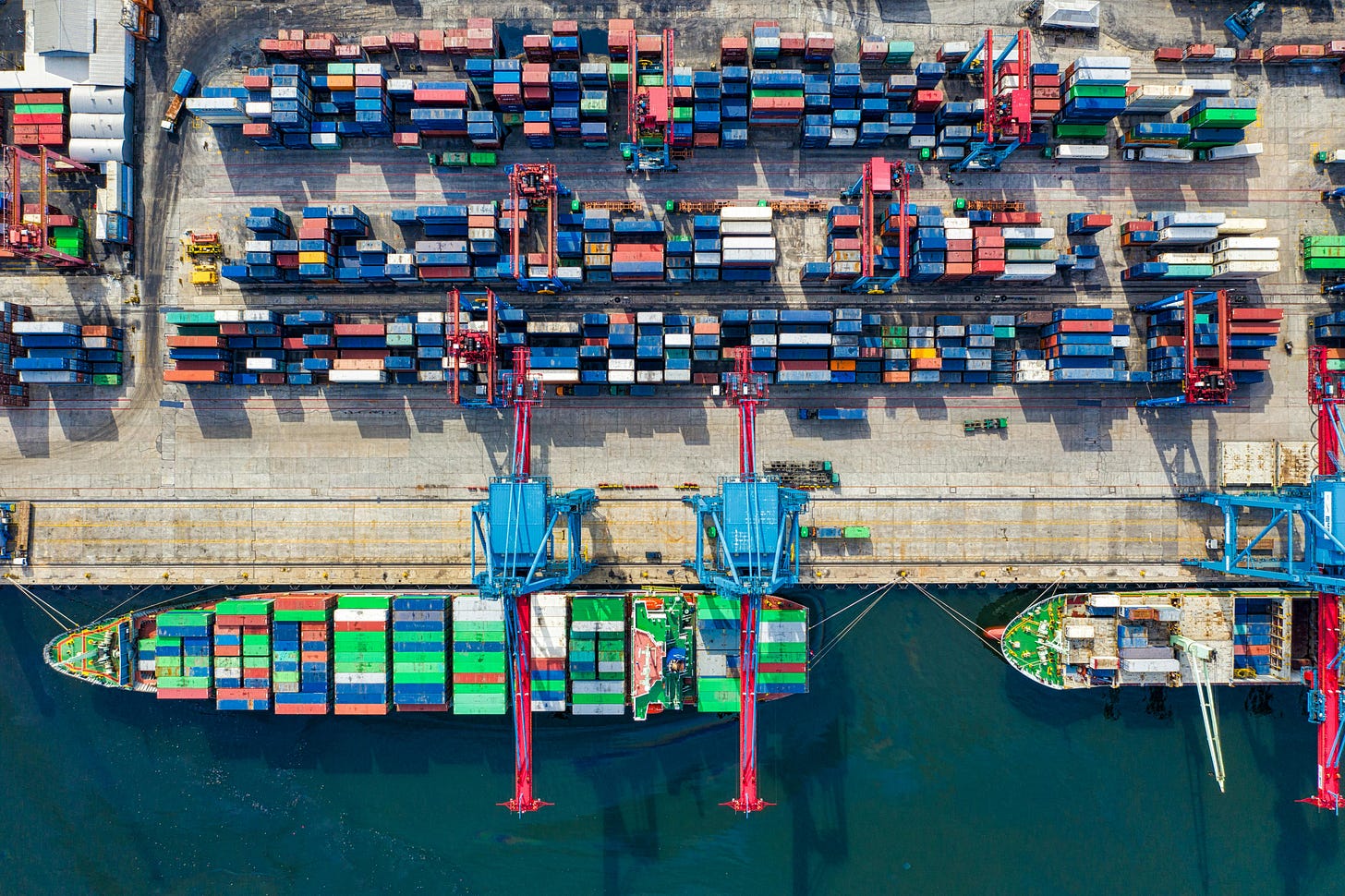

Tariff Law

According to an explanation given by the minister of justice to lawmakers, the Tariff Law (to take effect on December 1, 2024) was drafted with three goals in mind: (1) to implement the principle of “law-based taxation” [税收法定] (more on this below), as tariffs are now imposed by State Council regulations; (2) to introduce legal tools for responding to “changes in domestic and international situations”; and (3) to memorialize measures that simplify customs clearance procedures. Thus, the Law will codify the existing tax scheme largely as is so that “the tariff system is kept essentially stable and the overall tax burden remains unchanged,” while introducing new provisions necessary to achieve those three goals.

Here I’ll note only a few changes introduced by this highly technical statute:

The NPCSC now exercises greater oversight over tariff policymaking. For instance, most changes in tariff rates, once approved by the State Council, must be filed with the NPCSC. And NPCSC approval is required to change the tariff rates that China committed to in its protocol of accession to the World Trade Organization (art. 15, para. 1).

Relatedly, the Law vests the authority to set the amount of tariff-exempt inbound personal articles in the State Council instead of the General Administration of Customs (GAC) as is now the case (art. 5, para. 3). The GAC has set the amount at RMB 5,000 for residents and RMB 2,000 for nonresidents since 2010. One law firm speculates that the State Council will likely revisit—and raise—the thresholds once it promulgates new exemption rules under the Law.

The Law authorizes the State Council to take “corresponding measures based on the principle of reciprocity” when another jurisdiction “fails to comply with any clause on most-favored-nation treatment or on preferential tariffs” in a treaty that binds both it and China (art. 17).

The Law explicitly authorizes specified customs officials to impose exit bans on taxpayers who have neither fully paid the tariffs and late fees due, nor have posted bond (art. 49, para. 2). Officials of taxation authorities already have this power under the Tax Collection Administration Law [税收征收管理法].

I’ll note one final interesting feature of the Law. Under article 4, the PRC Import and Export Tariffs Schedule [中华人民共和国进出口税则] lists the goods subject to tariffs and sets the tariff rates and rules of application. Because the Schedule contains essential elements of the tariff that (under the principle of law-based taxation) must be provided in a statute, the Schedule was appended to the Law (thus made part of it) and approved by the NPCSC. But because the Schedule is also very lengthy (it has over 1,500 pages), highly technical, and modified frequently, the Law grants authority to the Customs Tariff Commission of the State Council to separately promulgate the Schedule as adopted (which it did) and as subsequently modified. This is a first in Chinese legislative practice.6

The Road to ”Law-Based Taxation“

“Law-based taxation” is the idea that taxes should be levied by a (nominally) representative body like the NPC and not simply by administrative edicts. The 2015 amendment to the Legislation Law [立法法] translated that principle into the rule that only statutes may prescribe “basic systems for taxation such as the establishment of taxes, determination of tax rates, and the collection and management of taxes.”

As I’ve recounted in detail here, the effort to achieve “law-based taxation” originates from the Communist Party’s 2013 Third Plenum. This initiative was necessary because in the early 1980s, the NPC granted the State Council substantial authority to pass administrative regulations on economic matters, including taxation. The result was that, by the Third Plenum, only 3 of China’s 18 taxes7 were imposed by statutes: the individual income tax [个人所得税], enterprise income tax [企业所得税], and vehicle and vessel tax [车船税].

Following the 2015 Legislation Law amendment, the Party approved (without disclosing) a plan to implement the principle of law-based taxation. But based on Xinhua’s interview with a legislative official, the plan essentially required the legislature to elevate all tax regulations into statutes by 2020, and then repeal the 1980s decision delegating legislative authority to the State Council.

Since then, the NPCSC has8—

enacted the environmental protection tax [环境保护税] in 2016;

substantially updated the Individual Income Tax Law [个人所得税法] in 2018; and

elevated into law nine tax regulations that governed, respectively, the vessel tonnage tax [船舶吨税] (2017), tobacco leaf tax [烟叶税] (2017), vehicle acquisition tax [车辆购置税] (2018), cultivated land occupation tax [耕地占用税] (2018), resource tax [资源税] (2019), urban maintenance and construction tax [城市维护建设税] (2020), deed tax [契税] (2020), stamp tax [印花税] (2021), and tariff [关税] (2024).

Despite all this progress, the 2015 plan was overly ambitious in retrospect. 2020 has come and gone, but 5 taxes are still governed by regulations today. A Value-Added Tax Law [增值税法] is pending before the NPCSC, which has just scheduled it for a third and likely final review in December. A Consumption Tax Law [消费税法] is a top-priority project in the 14th NPCSC’s five-year legislative plan but has yet to be submitted. The remaining three taxes—the building tax [房产税], land value-added tax [土地增值税], and urban land use tax [城镇土地使用税]—all concern land. It appears that any related legislation has been put on hold pending the pilot of a real estate tax [房地产税], which itself has been indefinitely delayed due to China’s struggling property market. So China’s long march to “law-based taxation” continues.

That’s all for this month’s issue. Thanks for reading!

If you wish to get all our coverage in your inbox in real time, subscribe here!

I previously translated “学位” as “academic degrees.” I now use simply “degrees” because the Law distinguishes between “学术学位” and “专业学位” (professional degrees), and the only acceptable translation of the former, it seems, is “academic degrees.” I trust that context will make it clear that it is not a law about the measurement of angles, arcs, temperature, etc.

According to Minister of Justice He Rong, the State Council found a total of six laws that must be updated to conform to last year’s institutional reforms. The bill passed last month amended only three because the others—the Trademark Law [商标法], the Law on the People’s Bank of China [中国人民银行法], and the Commercial Banks Law [商业银行法]—require (and have been scheduled for) comprehensive revisions.

In June 2022, the State Council requested authorization to allow mortgaging the right to use rural house sites [宅基地使用权] (which is otherwise prohibited by the Civil Code [民法典]) in selected localities. This appears to be a second attempt at the same reform that the NPCSC had previously authorized on a trial basis in late 2015. Because of the complexities of the reform (officials say), however, that pilot expired in late 2018 without being codified. Perhaps for similar reasons, the NPCSC did not vote on the State Council’s second request from two years ago and it remains pending today.

But if a candidate objects to any academic assessment made during the degree-conferral process, the Degrees Law allows for only one internal academic review by the institution and makes clear that the resulting decision is final (art. 40).

See 伏创宇 [Fu Chuangyu], 从《学位条例》到《学位法》:学位授予权的反思与重构 [From the Degrees Regulations to the Degrees Law: Reflections on and Reconstruction of the Degree-Granting Power], 当代法学 [Contemp. L. Rev.], no. 4, 2023, at 94, 95–97.

As far as I’m aware, the Macao Basic Law is the only other law that still allows a part of it (i.e., annex II, which governs the formation of the city’s Legislative Council) to be amended by an entity other than the national legislature. Even in this case, the annex was promulgated together with the Basic Law.

The Customs Law [海关法] authorized the collection of tariffs but didn’t specify the elements of the tax, which were instead prescribed by State Council regulations.

Thanks for the hard work you have put into this informative dispatch, and for your lucid English writing style dealing with complex Chinese texts.