March 2024: Previewing the NPC Standing Committee’s 2024 Legislative and Oversight Agenda

Recap of 2024 NPC session. NPCSC Legislative Affairs Commission's actions relating to Hong Kong’s Article 23 legislation. Plus: Mystery Bill Watch™ returns.

Welcome back to NPC Observer Monthly, a monthly newsletter about China’s national legislature: the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee (NPCSC).

Each issue will start with “News of the Month,” a recap of major NPC-related events from the previous month, with links to any coverage we have published on our main site, NPC Observer. If, during that month, we have also written posts that aren’t tied to current events, I’ll then provide a round-up in “Non-News of the Month.” Finally, depending on the month and my schedule, I may end an issue with discussions of an NPC-related topic that is in some way connected to the past month.

If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it. —Changhao

News of the Month

Starting with the main event last month: On March 5–11, the 14th NPC met for its second plenary session. At the closing meeting on March 11, it approved all reports and legislation submitted for review. All official documents from the session as well as the relevant vote results are compiled in this post:

Among the documents approved on March 11 was a revised State Council Organic Law [国务院组织法], which I have translated and annotated in this post:

This year’s NPC session was a rather mundane event, where the most notable news was probably something that did not happen: On March 4, the session’s spokesperson announced that the premier’s customary post-NPC press conference would be canceled not only this year, but “absent special circumstances” also for the rest of Li Qiang’s five-year term. Premier Li Peng held the first such press conference in 1988 and began doing so consistently during his second term (1993–98). Thus, the premier had been meeting with the press annually without interruption since 1993—until last month.

Below, I will return to the document I watch the most closely, the NPCSC’s annual work report.

On March 1, a week before the Hong Kong government introduced the Safeguarding National Security Bill into the Legislative Council (LegCo), the NPCSC Legislative Affairs Commission (LAC) responded to a legal inquiry from the city government on how to define the term “Central Authorities” [中央] in the Bill (the response was not posted online until March 9). In this post, we translated the response, explained why the definition of that term matters, and discussed the response’s potential broader implications.

On March 19, the LegCo voted unanimously to approve the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance. Later that day, a spokesperson for the LAC issued a statement applauding the law’s passage. The statement ends with the following:

Under [article 17] of the Hong Kong Basic Law, “[l]aws enacted by the [LegCo] must be reported to the [NPCSC] for recording.” Recording and reviewing the laws enacted by the [LegCo] is an important power vested in the NPCSC by the Constitution and the Hong Kong Basic Law. In accordance with the provisions of relevant laws, after the NPCSC receives a filing of the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance for recording, its relevant working body [i.e., the LAC] will conduct review in accordance with its statutory responsibilities and procedures and will report to the NPCSC on recording and review in due time.

根据香港基本法有关规定,香港特别行政区立法机关制定的法律须报全国人民代表大会常务委员会备案。对香港特别行政区立法机关制定的法律进行备案审查,是宪法和香港基本法赋予全国人大常委会的一项重要职权。根据有关法律规定,全国人大常委会收到报送备案的《维护国家安全条例》后,将由有关工作机构依照法定职责和程序进行审查,适时向全国人大常委会报告备案审查工作情况。

As I have recently explained when covering the NPC’s 2023 report on constitutional enforcement:

Under article 17 of the [Hong Kong Basic Law], if the NPCSC “considers that any law enacted by [the LegCo] is not in conformity with the provisions of [the Basic Law] regarding affairs within the responsibility of the Central Authorities or regarding the relationship between the Central Authorities and [Hong Kong],” it may “return” the law in question to [Hong Kong], thereby invalidating it immediately. The NPCSC’s review of [Hong Kong’s local] legislation is therefore doctrinally distinct from its review of mainland legislation (which is reviewable on broader grounds of constitutionality, conformity with [Communist] Party policy, legality, and reasonableness). Yet, since 2019, the NPCSC has incorporated, so far only rhetorically, the article 17 process under the Basic Law[] into the “recording and review” system that initially covered only mainland legislation.

The NPCSC has never “returned” (i.e., invalidated) any Hong Kong law and will not do so here, especially considering the city government’s aforementioned legal inquiry to the LAC and the congratulatory tone of the latter’s statement. By convention, the LAC reports to the NPCSC on recording and review each December, and the Ordinance may receive a special mention in this year’s report.

Reading the NPCSC’s 2024 Work Report

Like other state institutions, the NPCSC uses its annual work reports for two purposes: recapping, in a very positive light, its accomplishments of the previous year; and laying out its priorities for the upcoming year. Each section divides the NPCSC’s work into six areas: (1) constitutional enforcement; (2) lawmaking; (3) oversight; (4) work related to NPC delegates (so-called “代表工作”); (5) international exchanges (or “foreign/external work” [对外工作]); and (6) “self-improvement” [自身建设], a somewhat catch-all category that emphasizes efforts to uphold the Party’s leadership and capacity-building for NPC bodies.

Here, I’ll take a closer look at two areas that should be more interesting to casual observers: the NPCSC’s legislative and oversight priorities for 2024. What is included in the work report should be considered only a preview of the NPCSC’s agenda, however, as it could differ from its formal legislative and oversight plans for 2024, which won’t be finalized until late April. As for this year’s planned legislation, in particular, I expect the finalized annual legislative plan to include more projects than the work report, and a few of the projects listed below may end up being “backup projects” [预备审议项目]—ones that most likely won’t be submitted for review during the relevant year.

(The following is excerpted from the official English translation of the work report, with my edits.)

2. Improving the socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics. . . . We will compile a draft Ecological and Environmental Code [生态环境法典] to submit for deliberation.

To strengthen the institutions through which the people run the country, we will revise the Law on Delegates to the National People’s Congress and Local People’s Congresses [Delegates Law; 全国人民代表大会和地方各级人民代表大会代表法], the Law on the Oversight by the Standing Committees of People’s Congresses* [各级人民代表大会常务委员会监督法], the Supervision Law [监察法], and the Urban Residents’ Committees Organic Law [城市居民委员会组织法].

In order to accelerate the creation of a new pattern of development and deepen reform across the board, we will formulate a Financial Stability Law* [金融稳定法], a Rural Collective Economic Organizations Law* [农村集体经济组织法], a Value-Added Tax Law* [增值税法], and a Private Economy Promotion Law [民营经济促进法]; and we will revise the Mineral Resources Law* [矿产资源法], the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law [企业破产法], the Anti–Unfair Competition Law [反不正当竞争法], the Accounting Law*† [会计法], the Bid Invitation and Bidding Law [招标投标法], the Statistics Law*† [统计法], and the Civil Aviation Law [民用航空法].

In regard to advancing the strategy for invigorating China through science and education and the workforce development strategy and to building a strong culture, we plan to enact a Preschool Education Law* [学前教育法] and an Academic Degrees Law* [学位法] and revise the Science and Technology Popularization Law [科学技术普及法], the Cultural Relics Protection Law* [文物保护法], and the Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language [国家通用语言文字法].

With a focus on ensuring and improving public wellbeing and ensuring social stability and harmony, we will formulate a Civil Compulsory Enforcement Law* [民事强制执行法], a Law on Publicity and Education on the Rule of Law [法治宣传教育法], a Public Health Emergency Response Law [突发公共卫生事件应对法], and a Social Assistance Law [社会救助法]; and we will also revise the Arbitration Law [仲裁法], the Prison Law [监狱法], the Public Security Administration Punishments Law* [治安管理处罚法], and the Law on the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases* [传染病防治法].

To modernize China’s system and capacity for national security, we will enact an Emergency Response and Management Law* [突发事件应对管理法], an Energy Law*† [能源法], an Atomic Energy Law*† [原子能法], and a Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law [危险化学品安全法], while also revising the National Defense Education Law [国防教育法] and the Cybersecurity Law [网络安全法].

We will formulate a Tariff Law* [关税法], revise the Border Health and Quarantine Law* [国境卫生检疫法] and the Anti–Money Laundering Law*† [反洗钱法], and develop a system of laws for extraterritorial application in an effort to strengthen legislation in foreign-related areas. . . .

Bills already pending before the NPCSC are each marked with an asterisk (*); the five with daggers (†) were submitted by the State Council a few months ago and have yet to be listed on a legislative session’s agenda (but could be as soon as late April). The two bills that have already gone through two reviews—the draft Value-Added Tax Law and Emergency Response and Management Law—will most certainly pass in 2024, but it’s harder to predict for the rest. In addition, I expect the proposed changes to the Delegates Law to head to the NPC’s 2025 session and to pass then. And the draft Ecological and Environmental Code will come before the full NPC for a final review in 2026 or 2027, depending on the progress.

3. Taking solid steps to exercise effective oversight. Our oversight will focus on major decisions and plans laid out by the Party Central Committee, respond to the people’s concerns and expectations, and be oriented toward solving problems. . . . We have prepared 35 oversight projects for this year.

We will inspect the enforcement of five laws, namely the Law on the State-Owned Assets of Enterprises [企业国有资产法], the Agriculture Law [农业法], the Social Insurance Law [社会保险法], the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law [非物质文化遗产保护法], and the Yellow River Protection Law [黄河保护法]. . . .

We will hear and review a special work report on the management of government debt for the first time.

We will hear and review reports of the State Council, the National Supervision Commission, the Supreme People’s Court, and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on the work related to the private economy, allocation and use of government funds for disaster prevention and mitigation and emergency management, development of world-class universities and strong disciplines with Chinese features, childcare, eldercare, the environment, arable land protection, desertification prevention and control, the hearing of administrative cases, procuratorial oversight of administrative litigation, and elimination of misconduct and corruption that occur at people’s doorsteps [整治群众身边不正之风和腐败问题].

We will carry out special inquiries [a form of oversight hearings, as explained here] in conjunction with hearing and reviewing the reports on the development of world-class universities and strong disciplines with Chinese features and on the law enforcement inspection of the Yellow River Protection Law.

We will conduct topical research on financial services provided to support full rural revitalization; efforts in strengthening stability, security, and development in border areas in the New Era; development of agricultural socialization services [农业社会化服务]; implementation of the Budget Law [预算法]; management and reform of government procurement; safe urban development; implementation of the [NPCSC’s] resolution on the eighth five-year initiative to carry out publicity and education on the rule of law, and ways to make use of the strengths of Chinese nationals overseas [侨务资源]. . . .

As I’ve told The Diplomat magazine, these oversight reports are “[a]n overlooked authoritative source of information,” for they “often describe existing official policies and practices concerning particular issues, their shortcomings, and the authorities’ plan to address them.” The reports will all be made public except for the topical-research reports (the vast majority of which are reserved for internal reference).

I will end this post with a few wonkier observations about the NPCSC’s work report.

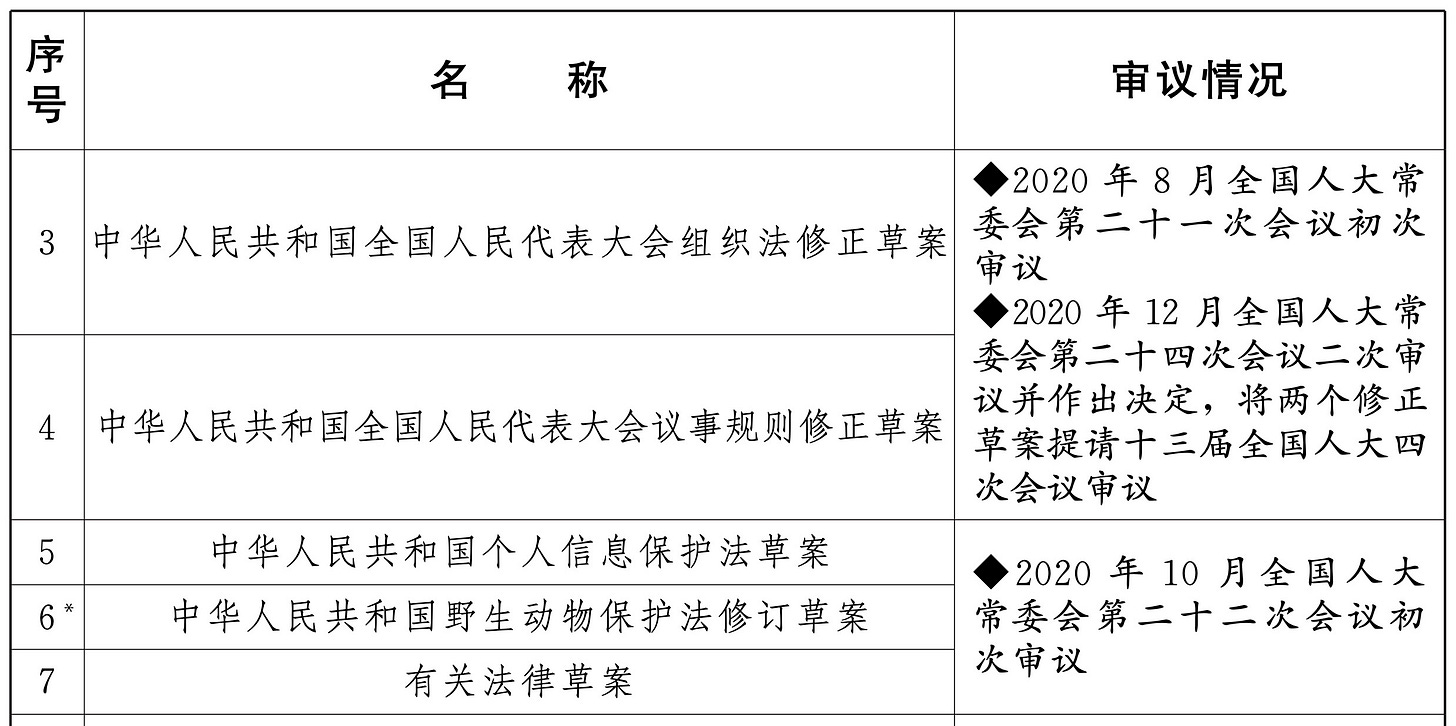

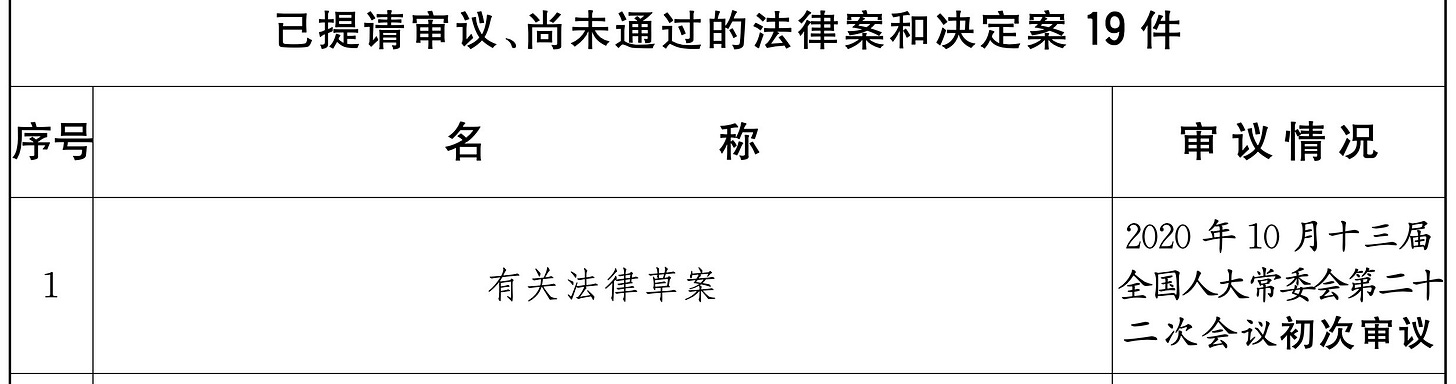

Legislative Transparency & Bill Deaths

Did you know that the version of the NPCSC’s annual work report that is handed to the NPC delegates includes various appendices that aren’t eventually made public when the report is finalized? I don’t think I realized that until 2021. And it was that year’s appendices that first disclosed the existence of what I’ll call the “Mystery Bill”: an unnamed legislative bill that the NPCSC reviewed in October 2020 for the first and (so far) the only time. The bill is referred to as “a relevant draft law” in the 2021 report (Fig. 1). Its existence has been then reconfirmed by the two subsequent work reports (see Figs. 2–3)—and, based on the 2024 report (see Fig. 4), it appears still pending (i.e., not shelved).

It’s impossible to say for sure what the Mystery Bill is. The NPCSC has taken great care to hide its title in official documents. In the itemized agenda of its October 2020 session, for instance, the bill was listed as the innocuous “other” [其他], the last (31st) item on the agenda.

But it’s possible to narrow down the possibilities a bit (the following largely rehashes this Twitter thread of mine from 2021):

It’s obvious that the Mystery Bill’s subject matter is sensitive in some manner and that the authorities would rather not provide advance notice to whoever would be affected by it.

It’s also obvious that the Bill’s title would adequately reveal what makes it sensitive. In this respect, I think the Bill would more likely enact a new law than amend an old one, because I can think of few laws that both could conceivably be undergoing amendment and are so inherently sensitive that the very fact of a pending amendment can’t be disclosed to the public.

Assuming the Bill would enact a new law, then its subject matter is most likely within the legislature’s exclusive legislative authority, for otherwise another body like the State Council that uses a more secretive legislative process could act instead.

The NPC and its Standing Committee have exclusive legislative authority over ten areas,1 four of which could, in theory, be relevant2: (1) matters of state sovereignty; (2) organization and functions of certain state organs; (3) the systems of special administrative regions; and (4) certain matters of taxation. Area #3 can be eliminated because there has been no media report of any proposed laws concerning Hong Kong or Macao (besides the ones that have passed). Area #2 is also less likely, because all laws concerning those state organs have recently been amended or scheduled for update and there is no reason to withhold the existence of a pending amendment.

My best guess, therefore, is that the Mystery Bill is a draft Property Tax Law (which was on prior legislative plans)—it’s not hard to see why the authorities might want to keep it hidden and why it has not moved forward since then (hint: the NPCSC authorized a five-year pilot of the tax in October 2021 that . . . has yet to begin). Or it could be a new law in Area #1, but in that case I don’t have a concrete idea as to what it might be.

Is the NPCSC allowed to hide the Mystery Bill from the public? you might ask. There was no clear legal basis for doing so in October 2020, though the NPCSC’s concealment of the Bill reflects a broader deviation from its prior transparency norm that, as I documented here, had already emerged in mid-2020. Later, the NPCSC amended its Rules of Procedure in June 2022, explicitly authorizing the withholding of select agenda items from the public.

You might also wonder whether the NPCSC can just sit on the Mystery Bill indefinitely. It couldn’t—not when the Bill was first introduced. Under the pre-2023 Legislation Law, once a bill was reviewed by the legislature, it must be reviewed again within two years, or otherwise it would expire (and the legislative process would have to start anew, if the bill was still deemed necessary). In the few times this provision was invoked, the bills at issue were considered either unripe or inadvisable, and very few3 were eventually enacted. The Mystery Bill therefore should’ve “died” in October 2022. But coincidentally, at that month’s session the NPCSC reviewed a draft amendment to the Legislation Law that (for the reasons I speculated here) would relax the mandatory expiration rule, so that a bill that has reached the two-year mark of inaction may be kept alive if the legislative leadership so decides. The amendment was approved in March 2023, and it appears that the Mystery Bill has retroactively benefitted from it.

That’s all for this month’s issue. Thanks for reading!

Here’s our preview of NPC-related events in April 2024. If you wish to get all our coverage in your inbox in real time, subscribe here!

Under Article 11 of the Legislation Law [立法法] as amended in 2023, the ten areas are:

(1) matters of state sovereignty;

(2) the establishment, organization, functions, and powers of the various levels of people’s congresses, people’s governments, supervision commissions, people’s courts, and people’s procuratorates;

(3) the system of ethnic regional autonomy, the systems of special administrative regions, and the system of basic-level self-governance;

(4) crimes and criminal punishments;

(5) deprivation of citizens’ political rights as well as compulsory measures and punishments that restrict physical liberty;

(6) basic systems for taxation such as the establishment of taxes, determination of tax rates, and the collection and management of taxes;

(7) expropriation and requisition of non-state-owned assets;

(8) basic systems of civil law;

(9) basic economic systems, and basic fiscal, customs, financial, and foreign-trade systems; [and]

(10) litigation systems and basic arbitration systems[.]

A fifth area—“basic economic systems, and basic fiscal, customs, financial, and foreign-trade systems”—could be relevant as well, but I can’t imagine a new law in this area whose title must be kept a secret and which wouldn’t have been swiftly passed.

For instance, a draft Decision on Improving the People’s Assessor System [完善人民陪审员制度的决定] was reviewed in October 2000 and expired two years later due to inaction. In April 2004, a decision with the same title (but with updated provisions) was again submitted for review and passed in August of that year.